By Fiona Moejes, Dahari

Data analysis. Statistics. As a student, I remember dreading these topics and I could think of a million things I would rather be doing (catching up on sleep for example). But they are also absolutely essential; without analysis, data are essentially just a bunch of random numbers that don’t mean much to anyone.

I work for Dahari – a Comorian NGO that, in partnership with Blue Ventures (BV), has developed a marine programme that supports fishing communities on the island of Anjouan to protect and preserve their marine resources.

We have been providing training to enable fishing communities to continuously record their catch data, and they now have a steadily growing and increasingly useful data set. However, without analysis and interpretation of this data set into a format that can be understood by the communities, it can’t provide the information they need to better manage their fishery.

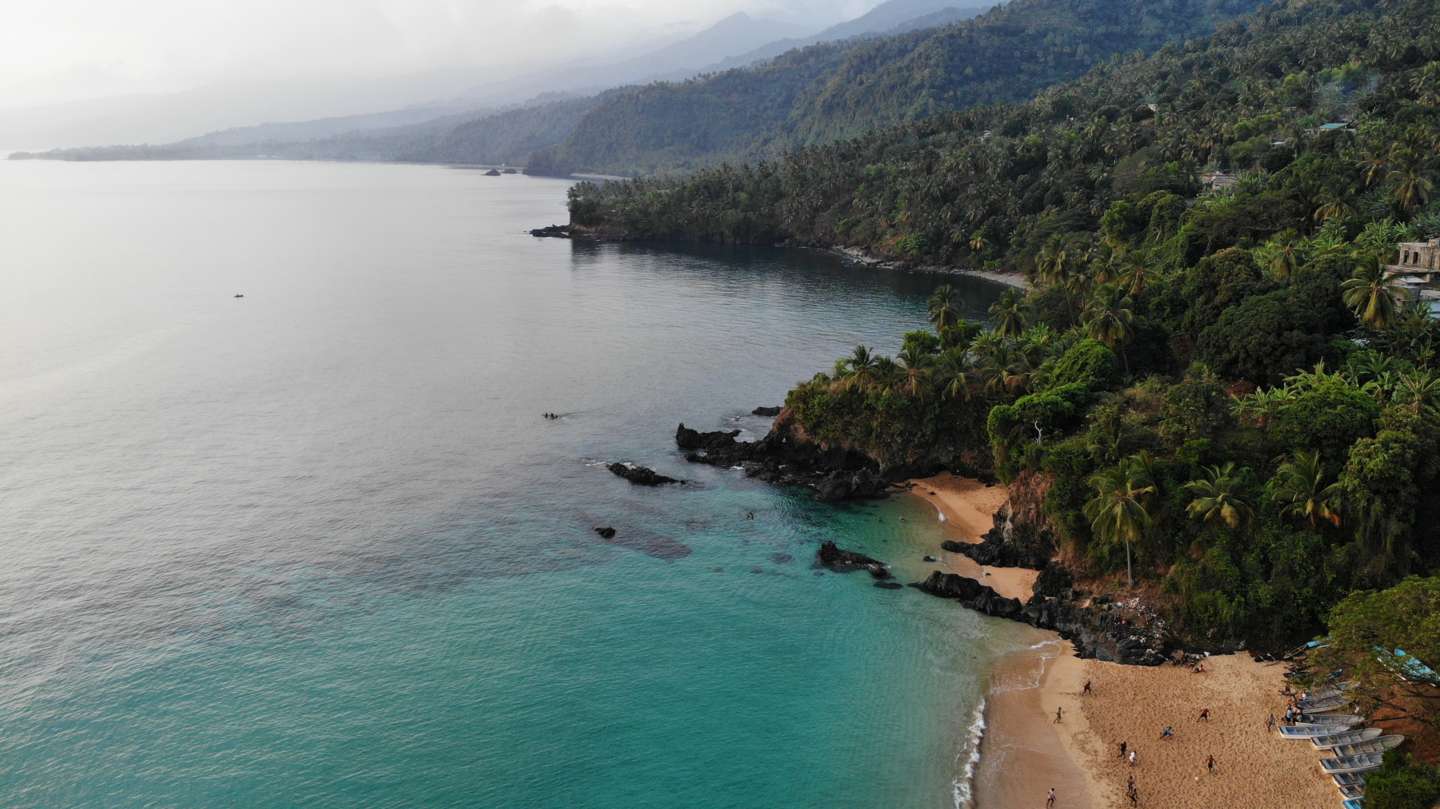

Anjouan | Photo: Matthew Judge

Currently the data are sent to a database managed by the Dahari team, who then turn the numbers into graphs that can be fed back and digested by the communities during regular feedback sessions. But this system was never the end goal.

Dahari’s approach is to support communities on the journey to complete ownership of their fisheries management. This autonomy will allow communities to collect, analyse and interpret their fisheries data, enabling them to make informed management decisions, and giving them greater leverage when selling their catch to global markets or when advocating for their management rights.

As the next step to supporting data ownership on Anjouan, Dahari and BV hosted a five-session crash course in data analysis. The 15 participants were all members of Maecha Bora – the local fisherwomen’s association who were responsible for organising the first community-led periodic fishery closure in the Comoros. They were all highly motivated to learn, which in combination with blue skies, a gentle breeze and the sound of the ocean in our ears, made for a very enjoyable experience.

Photo: Dahari

The training sessions included discussions on the benefits of catch monitoring, how to draw and interpret a graph, and how to use the analysed data to advise management. The women of Maecha Bora quickly realised that numbers and graphs were simply a way of formalising the analysis and discussion of seasonal trends that their communities have been doing for centuries.

The data analysis training showed me that our catch monitoring data resemble what we already know about octopus fishing. The months that we know are bad for octopus fishing were the months when octopus catches were the lowest.

By analysing this data, I am able to make management decisions, including when to do a periodic fishery closure in the future. Data analysis is complicated, but thanks to the training I better understand it.

Raydati Mirsoid, member of Maecha Bora

One of the methods we used to spice up these training sessions was to include a fishing game, based on a similar game used by BV in Madagascar. The participants were split into three groups of five and were provided with “fishing gear” (part of an old water bottle with a stick attached), a reef (a chalk circle on the ground) and octopuses (represented by sweets).

After shouting “Uloa!” (‘fish’ in Shindzuani), one woman from each group was given 30 seconds (representing a month) to catch as many octopus as possible, after which the remaining octopus would double. However, the women’s initial strategy of “take as much as possible” led to all the octopus being gone by the eighth round, representing a complete collapse of the stock.

Photo: Effy Vessaz

For the second attempt, each team was given some time to discuss management strategies and all three teams decided to close the reef for at least one month. This enabled every team to fish for the whole year i.e. finish the 12 rounds of the game.

During the game, the “catch” was monitored and the data used to build graphs by lining up all the sweets on graph paper. The participants then drew around the sweets to create a bar graph, allowing them to visualise what the bars were representing. Each group then presented their data and we discussed the results as a collective – including the importance of management measures.

When I first played the game with the sweets, I took as many as possible and realised nothing was left for me to catch after a few rounds. When we played the game again with management measures in place, I was able to catch sweets in all the rounds. This moment made me realise the importance of managing our marine resources, and why we do the catch monitoring.

Halouwa Toiybina, member of Maecha Bora

Since then, I’ve presented on overcoming barriers in technology literacy on Anjouan at the second ICT4Fisheries conference in Cape Town, and used this fishing game as a case study. It sparked a lot of interest from the conference participants, and I’ve since heard that conference host, and fellow BV partner – Abalobi – has used the game with small-scale fishers in Cape Town during a workshop on fisheries co-management.

Dahari wants to ensure that the people of Anjouan know that their fisheries data are theirs to collect, analyse and use as they see fit, and we will continue offering training in data literacy and analysis to support this journey. The data analysis crash course on Anjouan was a great start, and the next step is handing over the catch monitoring feedback sessions to Maecha Bora.

The training showed me the importance of data analysis. We know what is going on in the sea and people can now come to us and ask questions. We can also use our knowledge to help convince stubborn people to engage in sustainable fishing practices and management measures so that the next generation can also enjoy the goodness that the sea has to offer.

I hope that more women will join Maecha Bora so that we can have more people with the knowledge to support things like periodic fishery closures. I think we have to keep doing more training and learn more so that we can manage our oceans better.

Charifa Saidina, member of Maecha Bora

Read our previous blog from Comoros:

Behind the lens: how communities helped craft a global film about locally led marine management

We would like to thank the OAK Foundation, the Tusk Trust and the World Wildlife Fund for their support.

I find this extremely interesting and have been wondering if I could use this as an example in my teaching (MSc’s in Conservation and also Marine Ecosystem Management at St Andrews). We talk a lot to the students about the difficulties of communicating our science – here is a super way to do it.

Could you possibly put me in touch with someone who might be able to help?